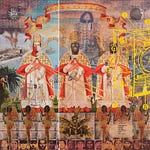

Rafael Trelles was born in the Santurce neighborhood of San Juan in 1957 and began studying painting at the age of eleven under the instruction of Catalan painter Julio Yort. In 1980, Trelles graduated from the Universidad de Puerto Rico with a degree in Fine Arts, magna cum laude. In 1983, he pursued graduate studies at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). His work has been exhibited internationally including in New York, Florida, Mexico and in a major exhibition in 2018, Santurce, un libro mural, at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Puerto Rico. He resides and works in San Juan, Puerto Rico and I was happy to have the opportunity to speak with him regarding the trajectory of Puerto Rican art and the struggle to safeguard the island’s cultural heritage amid political and economic pressures. This translation of our conversation in Spanish has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Can we talk a little about the artistic environment that influenced you while growing up in Puerto Rico?

As you noted, first I started with Julio Yort. My training was in academic painting until I entered university and I started taking classes with the professors who taught at the Universidad de Puerto Rico and there I had access to great Puerto Rican masters and also masters from the United States who taught there. Then I entered fully into the language of contemporary art.

And who were some of your main artistic influences?

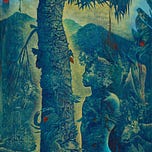

Well, in Puerto Rico I was influenced by Carmelo Fontánez, who was my teacher and who is still alive and is a great friend. He is a master of abstract art in Puerto Rico. Later, I can tell you that my greatest influence was Carlos Raquel Rivera, a painter from the town of Yauco. He was from the generation of the 1950s and he developed a surrealist, symbolic language…More within magical realism. He developed a whole landscape and a fantastic figuration full of symbolism, very connected to the traditions of the native peoples and also a simultaneously political work of social criticism and reflection on the political situation of Puerto Rico. In some way, I feel that I am a generational continuation of the work that Carlos Raquel Rivera did. And I have continued to develop a language also within what we call magical realism in literature or fantastic painting.

How have you seen the artistic environment in Puerto Rico change in recent years?

Puerto Rico is very connected through the internet, above all, and also through trips that Puerto Rican artists have made with international art currents. Here you will see that neo-conceptual art and other currents are very much in vogue. Young people no longer think in terms of what we call “Puerto Rican identity” or “art of national affirmation.” No, they are - they feel - Puerto Rican, but they are working with completely international languages and putting forward their ideas without necessarily making reference to a reality of the country.

There are also artists who are using their art to reflect on the reality that we have to live. There are also many Puerto Ricans who are working outside of Puerto Rico. We can say that we are in the moment of greatest internationalization and of the greatest vitality of Puerto Rican visual arts. And that has its historical explanation, right? Right now, in Puerto Rico, there are various art schools of visual arts whereas before there were just one or two. And these students are students of a generation that was educated outside of Puerto Rico, like me. We come back and then we can impart a broader vision of the world.

Puerto Rico is very connected today, yes, but, in your analysis, what does the artistic tradition - visual, musical, literary - of Puerto Rico say about Puerto Rican identity today?

Well, look, it is a very controversial topic in Puerto Rico, because as you well know, we are a colony and that sense of belonging, identity, has been one of the central themes of Puerto Rican art. From the 50s, the 60s, 70s, let's say, up to the 80s, it was one of the greatest concerns of Puerto Rican artists to be able to express in some way the identity of Puerto Rico. But today there are other currents of thought…Puerto Ricans have demonstrated a cultural vitality [and] nowadays we question the traditional notions of what identity is. We can say that there is not just one Puerto Rican identity, there are multiple identities. Puerto Rico is diverse. It is not the same, let's say, for a Puerto Rican, for a young person who grows up in a public housing project [as it is for someone] who is middle class and has the opportunity for an education. Or for a Puerto Rican who lives in New York or any other state in the United States. In other words, “Puerto Rican” has become a very broad and rich notion [and] each person interprets it and can express it in a different way.

Can we talk a little about the attempt by Puerto Rico's ruling party, the Partido Nuevo Progresista - perhaps poorly named - to subjugate the Instituto Puertorriqueño de Cultura (ICP) under the Department of Economic Development? Why, in your analysis, is this a priority for them and what are the possible impacts of this?

Well, there are really three purposes. Although when one reads the project, it says that it is to help culture and contribute to making culture with economic value, right, [so that] it contributes to the economy of Puerto Rico. That is not really the purpose. When one reads the bill, it is clear that the purpose is to take away from the Institute the supervisory powers that it has to recommend - or not - that construction be allowed in places whose value may be historical or patrimonial.

Those powers of the Institute are very important because, thanks to that, for example, Viejo San Juan preserves an authenticity in terms of its colonial architecture. And to the extent that these powers are passed to the Department of Development [we would have] an entity that promotes development while at the same time supposedly being the one that limits development through considerations of heritage.

Apart from the Institute, which has the experts in heritage and archaeological architecture, for example, right now a huge project is going to be built or has been proposed to be built in Cabo Rojo, which is in the southwest of the island. A huge project of hotels and luxury residences which will occupy a large part of the coastline [in a] a place of great ecological and archaeological value. There are more than 30 archaeological sites there that would be impacted by this construction. If the Institute goes in there, it will stop those constructions, because, according to the law, each of those projects is supposed to be investigated first and its archaeological value determined before building. As there are so many, well, this would imply that that project would be stopped for years. The way they are proposing to eliminate the Institute, it would be the same Department of Economic Development where the permit office is, which would give what we call here, taken from English, a “fast track.” Everything would be fast so that there would be no limit.

The second objective of the project is that the properties of the Institute would pass to the Department of Economic Development. Here we are also talking about dozens of properties that the Institute has, historic buildings of high value on the market, above all, for example, the headquarters of the Institute itself. It is a beautiful building and already last year the governor who was in power proposed moving the Institute to another place so that that building could be converted into a hotel. So there is an interest in appropriating these heritage properties to give them to developers and then convert them into private projects.

The third objective is really to attack the cultural sector of the country, which has always been a sector against statehood…The political history of Puerto Rico is full of many attempts by the pro-statehood party (or as we call it, the annexationist party) to destroy the Institute, so here there is also an ideological purpose to dismantle the Institute, because it has always been, along with the Universidad de Puerto Rico, the two entities that have become an obstacle to achieving statehood. Note that there are two economic objectives and one ideological one.

How can is it possible to combat these measures in Puerto Rico?

Well, right now it is difficult because they have the majority. When I say they, I mean the Partido Nuevo Progresista, which is the party that promotes statehood and that has a neoliberal agenda of development above any ecological or cultural limitation. And they have the power…What we have left is the street and a resistance movement and public demonstrations so that it is very costly, politically speaking, and they decide not to do it simply for partisan political considerations…Because the Institute is an entity that is very dear to the Puerto Rican people, even to the people who vote for the Partido Nuevo Progresista. They are people that, if you interviewed them, they will say that the Institute should not be eliminated because it is an institution that has contributed a lot to the development of Puerto Rican culture. In fact, a television station conducted a survey where they asked people where they asked people if they wanted the Institute to be eliminated and 96% said no, so it really is a measure that it is not very popular and there would be a sector that opposes it. We have to take advantage of that circumstance to create a people's movement that is above the political parties to defend the Institute.

And finally, what is your advice for young creatives in Puerto Rico?

Well, for creatives in Puerto Rico, I would say [it is the same] for those from anywhere in the world. I think that the first obstacle, the great obstacle that we have, is the power that the market has today. The market in all areas, as you know, has developed a power and an extraordinary hegemony…And for a young artist, it’s very easy to fall into the temptation of working based on what the market demands or asks for based on what is in fashion, based on what sells…And that would be very tragic, right?

To the artist, my recommendation is for young artists to work based on their personal goals, that they seek to develop a work that responds to their inner self, to their concerns. That it responds to the research they do, of any kind, because art can be based on historical, political, economic research [and] that they develop their own technique based on their own authenticity, that they develop honesty as an artist. I am sure that this work will have an impact and will please the public and therefore it will be sellable, but the fact that it is sellable, this will be a consequence of having an authentic work, a powerful work that responds to the internal concerns of the artists, not the other way around. If the artist, then, decides to give himself over to fashion, then he will have a work that he can perhaps sell, but that success will be really very temporary, no? The artist's job really is to be a spokesperson for himself first, for his internal concerns, but also to be a spokesperson for the society that welcomes him.

Thank you, Rafael, and good luck to you and the island, as well.

Thank you for the interview. And thank you also for your interest in Puerto Rico.

Share this post