The policemen were ranging through the cool, wooded climes of Métivier, a suburb of the once-fashionable Pétionville area of Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince. The once-peaceful hills above the nation's ramshackle, colourful largest city have been the scene of roiling criminal anarchy in recent years, of a piece with the general collapse of security in the metropolitan region. The patrol was said to be coming to the aid of the relative of one of their members, who had been targeted by one of the armed gangs that exact their will in Port-au-Prince with nearly total impunity. The force was quickly overwhelmed by the heavily-armed gangsters, though, with requests for backup going unresponded to for over an hour. When the shooting was over three policemen lay dead, one of their bodies set aflame. Another officer remains missing.

Garry Desrosiers, the spokesman for the Police Nationale d'Haïti (PNH), said the officers had been targeted by the Krazé Barrière (Gate Breakers) gang of Vitel'Homme Innocent, a former entrepreneur who allegedly worked together with another gang, the 400 Mawozo (400 Hillbillies), based in the northeastern suburb of Croix-des-Bouquets, to effect the October 2021 kidnapping of 17 missionaries. The latter adventure resulted in Innocent and 400 Mawozo leader Joseph Wilson (aka Lanmo San Jou or Death Comes Unannounced) getting a $1 million price put on their heads by the United States Department of State’s Transnational Organized Crime Rewards Program. This past spring, a failed attempt by the 400 Mawozo to seize the territory of a rival gang, the Chen Mechan (Mad Dogs), in the Plaine du Cul-de-Sac, killed at least 191 people, according to the human rights organization Réseau National de Défense des Droits Humains (RNDDH). Thousands more were displaced. Workers in the disputed area described to me how they were treated to the macabre spectacle of piles of bodies at intersections and the heads of 400 Mawozo members impaled on pikes by the roadside in an attempt by the Chen Mechan to frighten them away.

The Métivier killings were not even the most lethal attack against police that month. Last week, the Gran Grif gang in Haiti's Artibonite Valley agricultural region to the north of Port-au-Prince released video of the naked corpses of six police officers they had killed, which prompted days of rioting by police in the capital and elsewhere. A report released this month by the United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH) showed the number of homicides in the country increased by 35.2% during 2022 from the previous year, while the increase in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area was a stunning 81.6%. Nationwide, cases of kidnapping increased 104.7% in 2022.

“We are experiencing institutional chaos and humanitarian and social disaster,” Jacky Lumarque, the rector of the capital’s Université Quisqueya, told me one morning after I had driven to see him through streets eerily absent of pedestrians and almost completely devoid of children. “This political class doesn’t represent anything and there is no reason to trust the international community because they rarely do what they say and they rarely say what they do.”

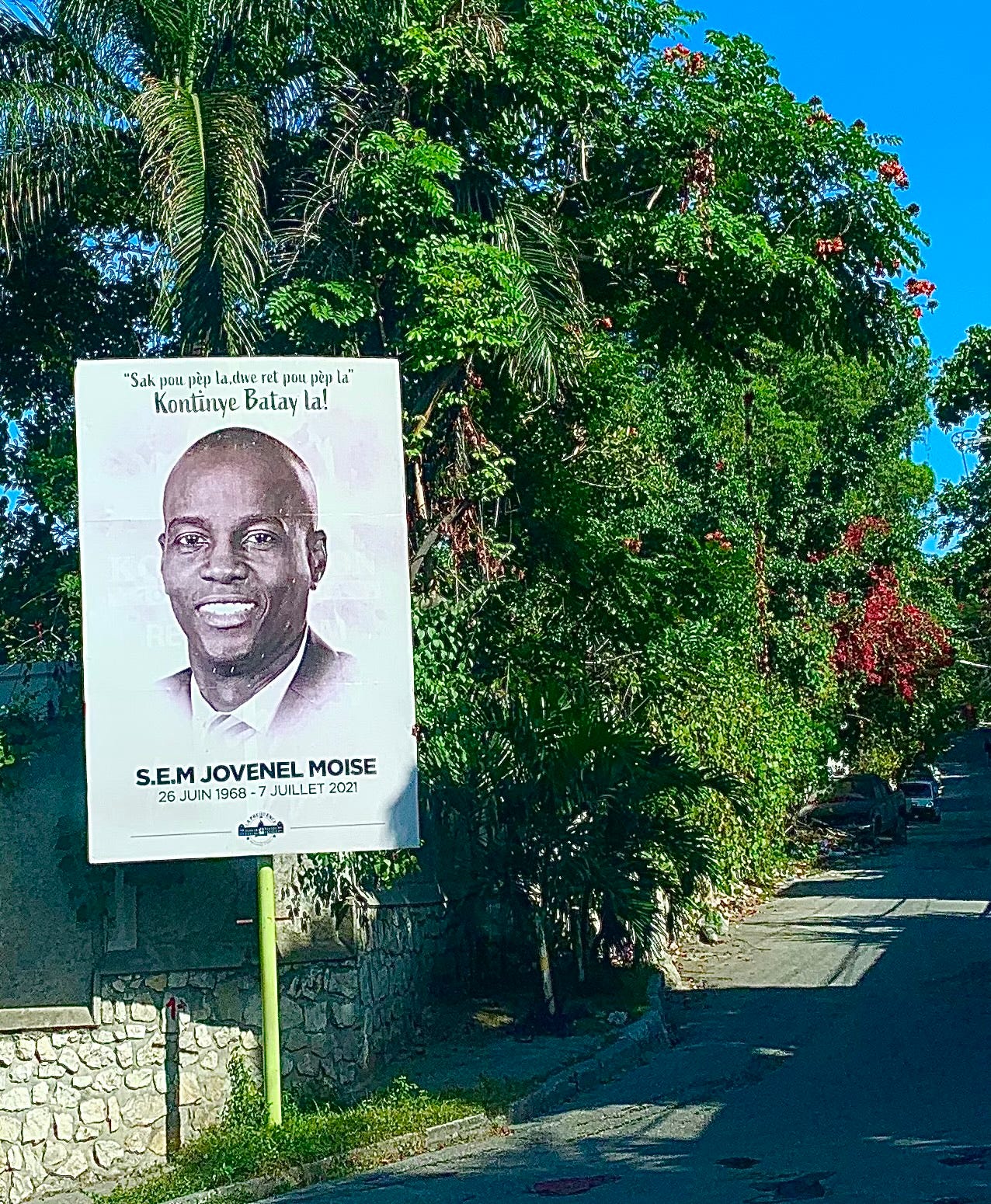

Haiti’s president, Jovenel Moïse, was assassinated by a hit squad in his home in July 2021, part of a complex, multi-country conspiracy for which no one has yet been tried. [Four men - three dual Haitian-American citizens and a Colombian - were recently charged for their alleged role in the crime in the United States.] Following Moïse, Ariel Henry, who Moïse had selected but who had not been confirmed as Prime Minister, took the reins of power in the nation. The fact that Henry clearly had a close relationship with Joseph Felix Badio, a fugitive currently wanted for questioning in connection with Moïse’s killing - including receiving phone calls from him directly before and after Moïse was murdered - appears to be something the international community would just rather not talk about. Before Moïse was killed, in January 2020, the terms of most of Haiti’s elected parliament had expired when his government and Haiti’s opposition couldn’t agree on a process to hold elections. An agreement by a group of civil society actors and veteran political chancers called the Montana Accord (named after the hotel where the group met) saw a handful of people undemocratically “elect” their own president and prime minister before largely falling apart. As of early January of this year, when the mandate of what was left of Haiti’s senate lapsed, there are no longer any elected officials anywhere in the country. Democracy in Haiti has been erased.

Université Quisqueya’s campus sits just near my old Port-au-Prince neighborhood of Pacot, where lovely if deliquescent gingerbread houses sit wreathed by sprays of bougainvillea. In recent years, the zone has become prime hunting ground for the kidnapping gang from the nearby district of Grand Ravine (part of the larger neighborhood of Martissant), led by Renel Destina, better known as Ti Lapli (Little Rain), currently sought by the FBI under a hostage-taking indictment filed in the District of Columbia. For the last several years, Destina and another crime boss, Izo, who runs the 5 Segonn (5 Seconds) gang from the nearby Village de Dieu slum and releases rap videos via a YouTube channel, fought a horrific war of attrition to try and oust a rival gang boss, Chéry Christ-Roi (known as Krisla) from the neighborhood of Ti Bois before, without explanation, declaring a truce this past December and calling on the many thousands who had fled the southern reaches of Haiti’s capital to return. Many believe the truce is little more than an attempt to coax back some convenient human shields as the gangs continue with their criminal business.

Over whiskey one night, a local businessman described to me how, when transiting Martissant “you have to pay [the gangs] for each container and there’s no guarantee” and then relating a story about how, when his company once failed to pay the required extortion, a truck containing 9000 gallons of fuel was “lost” and appeared 12 hours later empty. One company who deals in purified water sells water to intermediaries who then pay the tax to the Martissant gangs to take it onward to the south of the country. In many ways, Haiti’s police force has become the largest private security company in the nation. To transit cargo from Port-au-Prince to the northern city of Gonaïves requires three different police escorts, costing about $2,000 each. During a recent visit to Haiti, I found employees of the Banque de la République d'Haïti - the nation’s central bank - working diligently in the corner of the restaurant of a hotel because the bank’s offices along downtown’s Rue Pavée are in the midst of a gang war zone.

Though both the UN mission on the ground in Haiti (which has been accused of excessive closeness to both Henry and Moïse before him) and the UN’s Secretary General Antonio Guterres have spoken of the “urgent need” to deploy some sort of peacekeeping operation in Haiti (the last peacekeeping mission, whose success was mixed at best, only left in 2017), there seems to be little appetite in the hemisphere for anyone to actually lead it, with both the United States and Canada blanching at the prospect.

“We are all going to die here,” one merchant told me matter of factly one night, as he sat smoking a Dunbarton cigar behind the walls of a compound where several families have moved to seek safety in numbers.

Even before Jovenel Moïse’s July 2021 assasination, Haiti was already experiencing a precipitous decline in its security situation.

Elected as the candidate of the Parti Haïtien Tèt Kale (PHTK) created by former president Michel Martelly, Moïse inherited a political landscape populated by a recalcitrant opposition dominated by violent opportunists who promised to “destroy the country completely” if he took office and his own political current, whose links to criminality were both public and longstanding. Gunmen regularly cut down both government supporters and critics and large-scale killings in the capital’s poorest quarters, which some charged were linked to his administration, happened with alarming frequency. Moïse made a lot of enemies during his time in office, especially among the country’s business oligarchy, which had once helped him get elected but who began to hate him when he started to move against their interests. He railed against what he charged was the “capture” of Haiti’s state by such figures, and government-aligned magistrates issued a slew of arrest warrants, including against wealthy businessman Dimitri Vorbe, whom company, Sogener, Moïse accused of illicitly profiting from government energy contracts. Vorbe subsequently fled to Miami, but after Moïse’s killing, Ariel Henry helpfully selected one of Sogener’s lawyers, Berto Dorcé, as Haiti’s Minister of Justice. Dorcé and another official of the Henri government, Minister of Interior Liszt Quitel, would subsequently resign and be sanctioned by the Canadian government, which charged the pair used their status to protect and enable the illegal activities of armed criminal gangs through activities such as money laundering and other means.

“The economic situation is the worst we’ve seen in 30 years, but when you are elected president, you have a responsibility not only towards the people who elected you but to the legislature,” says Etzer Emile, a Haitian economist. “When you are a de facto Prime Minister with no parliament you have no accountability to anybody. Ariel Henry doesn’t have a mandate, he doesn’t have congressional validation, but he doesn’t care. He is just working to stay in power as long as he can.”

In the early 2000s, when I was living in Port-au-Prince, I witnessed the first advent of the gangs, as then-President Jean-Bertrand Aristide and his Fanmi Lavalas party helped arm and organize various youth gangs, many of them led by young men who had grown up in the orbit of the Lafanmi Selavi home for street children that Aristide had run when he was a priest. The gangs, many of the young leaders of which I knew personally, became a kind of praetorian guard to defend his regime. Aristide and Lavalas are now in political eclipse, but that template thereafter metastasized throughout Haiti's body politic until virtually every political grouping (and many in the business sector) had their baz or armed enforcers, a reality the international community has only seemed to wake up to relatively recently. A rain of international sanctions have descended upon Haiti’s rich and powerful in recent months, many of whom were thought to be untouchable for years. One international diplomat described that steady drumbeat of sanctions to me as “like opening an advent calendar.”

In November 2022, the U.S. Department of Treasury sanctioned the then-prersident of Haiti’s rump senate Joseph Lambert and former senator and veteran political leader Youri Latortue under an order targeting “foreign persons involved in the global illicit drug trade.” In November, the government of Canada sanctioned former President Martelly and former Prime Ministers Laurent Lamothe and Jean Henry Céant for their alleged involvement in financing armed gangs in country. [Lamothe charged the sanctions were “a political lynching.”] In December, Canada added three of the wealthiest members of Haiti’s economic elite - Gilbert Bigio (a billionaire), Reynold Deeb & Sherif Abdallah - to its list of sanctioned persons, saying they were doing so “in response to the egregious conduct of Haitian elites who provide illicit financial and operational support to armed gangs.” The United States followed the same month by sanctioning former deputy Rony Célestin and former senator Hervé Fourcand, both members of Martelly’s PHTK party for “abusing their power to further drug trafficking activities across the region,” as well as the former head of Haiti’s lower house of parliament, Gary Bodeau. Romel Bell, the former Director General of Haiti’s Customs was also put on the blacklist for “abusing his public position by participating in corrupt activity that undermined the integrity of Haiti’s government.” In January, Canada sanctioned Martelly’s brother-in-law Charles "Kiko" Saint-Rémy and former deputy Arnel Bélizaire (who frequently paraded around the capital armed while in office), charging they are "using their status as prominent members of Haiti's elite to protect armed criminal gangs."

“Even the people fighting today, we cannot say that they are the main ones responsible, they are instruments that are used,” says Jean Dadimy Cupidon, who grew up in Martissant and is today affiliated with Lakou Lapè (the name means “peaceful community” in Creole), a group whose mission is the promotion of a culture of non-violence and dialogue. “The politicians and the private sector…use these men, they play on their weaknesses, their precariousness, they make a series of things available to them, like weapons, like bullets, so, come election time, they control the neighborhoods and they win.”

But the gangs also began to begin to become too powerful for even their elite masters to control. Since September 2020, a violent land war has raged in the once-tranquil mountain community of Laboule 12 above Port-au-Prince, as paramilitary forces under the command of a wealthy lottery bank owner, Jean Mossanto Petit, known as Toto Borlette, and an armed group under the command of a young gang leader nicknamed Ti Makak that has seen dozens of murders, decapitations and the displacement of hundreds of people. This past October, the conflict saw the slaying of Eric Jean Baptiste, a veteran politician and leader of the Rassemblement des démocrates nationaux progressistes (RDNP) political party. Earlier last year, Yvon Buissereth, a former senator, and journalists John Wesley Amadi and Wilguens Saint-Louis, were also killed. Ti Makak is linked to the gang leader of Ti Lapli while several people knowledgeable about the situation spoke about links between Toto Borlette and PNH Director General Frantz Elbé.

“It feels there is a kind of omerta (code of silence) in the private sector not to talk about the overall situation of the country,” says Delphine Gardere, the owner of Rhum Barbancourt, which has operated in Haiti since 1862. “We are currently at a huge crossroads, where the private sector needs to take responsibility and stop the business malpractices that have been hindering social and economic development. It is time to have an honest dialogue with credible new voices from the private sector that truly want change and are ready to take action for a new and better Haiti.”

There is also a direct line between the violence in Haiti and the United States, as well. This past July, a ship arriving from Florida at the northern Haitian city of Port-de-Paix was discovered to be carrying 120,000 cartridges, three handguns, 30 magazines, 20 Ak-47s and $3,890. A few days later at the same port, seven illegal pistols were confiscated from another ship from the U.S. The Henry government responded by freeing two of the men who had been arrested for alleged involvement in the scheme and firing the official who’d overseen seizure of the weapons. Several suspect containers at a wharf in Port-au-Prince were also found to contain 9mm pistols, 14,646 cartridges, 140 magazines and 18 assault rifles.

“The situation we are living in now is a situation of generalized violence,” says Jean-Philippe Marcdy, a community leader also working with Lakou Lapè, who hails from the neighborhood of Bel Air, which rises in the hills in front of where Haiti’s gleaming white National Palace stood before it collapsed in the country's 2010 earthquake. “When we look, where are these weapons coming from? Where does this ammunition go? It's not the community that doesn't want the country to move forward, it is the mode of operation, the irresponsibility of the state…We need another political class because from the 1990s to the present day, they are the same.”

The night I left Haiti, Port-au-Prince showed another face. As on every Sunday evening in the runup to carnival, thousands of revelers packed the streets to sing and dance behind a sound truck in a cathartic release as a blanket of stars twinkled above the tropical palms. For a few hours, at least, Haiti’s ghosts seemed held at bay.

All photos by the author.