The Massacre in Haiti You’ve Never Heard Of

Why the Ghosts of La Scierie Should Still Haunt Us Today

Today, 11 February 2024, is the 20th anniversary of a terrible massacre that took place in and around the La Scierie neighborhood in the central Haitian city of Saint-Marc in February 2004.

Eventually claiming at least 27 lives, it remains one of the largest political massacres to take place in the Americas in the 21st century, though one that remains almost unknown outside of Haiti itself and one for which no one, from the politicians and intellectual authors involved in the crime to those who actually committed it, have ever been tried or sentenced. In the years since the La Scierie massacre took place, it has largely been ignored by foreign journalists, human rights organizations and diplomats, while many of those most closely connected with it in Haiti itself have seen their political ambitions and careers rehabilitated, with one even ascending to the presidency itself.

This is the story of the unquiet dead of La Scierie, and what they can tell us about Haiti today.

I. The Centre Cannot Hold

In February 2004, Haiti was in a state of intense and terrifying upheaval. Jean-Bertrand Aristide had been returned to the presidency in November 2000 elections along with a commanding parliamentary majority for his Fanmi Lavalas political party in a ballot that previous May which observers said had been achieved through fraud. Government critics were regularly harassed and sometimes killed and opposition party headquarters burned down. Cross-border attacks on government sites and loyalists, many by men under the sway of a dissident former police commander based in the Dominican Republic named Guy Philippe, were the order of the day. The Aristide government increasingly promoted and relied on armed gangs of poor youths from the most disenfranchised neighborhoods of the capital and elsewhere as a kind of praetorian guard and sledgehammer against its ever-expanding list of enemies, undercutting the law enforcement role of the Police Nationale d'Haïti (PNH), which had been constituted to, in theory, replace the Haitian army that had been disbanded in 1995. A number of these young men who formed the baz, or base, of the government’s armed groups, then known as the chimere, after a mythical fire-breathing demon, had grown up in the orbit of Aristide’s Lafanmi Selavi home for street children (the president was a former priest) and been gradually seduced into a life of violence in support of his political movement following his 1994 return to Haiti by U.S. troops.

However, it was among these very armed groups that a rebellion had begun in earnest against the government in September 2003 following the murder of Amiot Métayer, the leader of a particularly fierce armed group known as the Lame Kanibal (Cannibal Army) from the Raboteau slum in the northern city of Gonaïves. Métayer, a longtime Aristide partisan with a history of brutalizing government opponents in the city, had been briefly arrested in August 2002 before being broken out of jail by his gang in spectacular fashion shortly thereafter and returning uneasily to the government fold.

With the Organization of American States (OAS) demanding Métayer’s arrest, on 21 September 2003, he drove off from his base in Raboteau in the company of a former official of the Ministry of the Interior. The following day, Métayer’s body was found, his eyes carved out. Believing their leader had been murdered by the regime, mass demonstrations among the Lame Kanibal and others erupted in Gonaïves, only to be brutally dispersed by government forces. During Métayer’s funeral, hundreds of protesters chanted “Down with Aristide!” and clashed violently with police. A 2 October 2003 raid on Raboteau and nearby Jubilé by government security forces killed at least 15 people. The Lame Kanibal transformed into the Front de Résistance des Gonaïves. The Front fought vicious battles against government security forces in Gonaïves for three months until, in February 2004, a group of rebels led by Guy Philippe and former army officer Louis-Jodel Chamblain crossed into Haiti from the Dominican Republic and joined their cause.

II. Clean Sweep

On 7 February 2004, just south of Gonaïves in Saint-Marc, an armed anti-Aristide group, the Rassemblement des Militants Conséquents de Saint-Marc (RAMICOSM), based in the neighborhood of La Scierie, attempted to drive government forces from the town, seizing the local police station, which they set on fire. Two days later, on 9 February, the combined forces of the PNH, the Unité de Sécurité de la Garde du Palais National (USGPN) – a unit directly responsible for the president’s personal security – and the local pro-government paramilitary organization Bale Wouze (“Clean Sweep”) retook much of the city.

By 11 February, Bale Wouze – headed by Lavalas former deputy Amanus Mayette – had commenced the battle to retake La Scierie itself. At Mayette’s side was a government employee named Ronald Dauphin, known to residents as “Black Ronald,” often garbed in a police uniform even though he was in no way officially employed by the police. Other members included Figaro Désir, Biron Odigé and a man known as Somoza. After government forces retook the town – and after a press conference there by Yvon Neptune, at the time Aristide’s prime minister and the head of the Conseil Superieur de la Police Nationale d’Haïti (CSPN) – a textbook series of war crimes took place.

Residents told me of how Kenol St. Gilles, a carpenter with no political affiliation, was shot in each thigh, beaten unconscious by Bale Wouze members and thrown into a burning cement depot, where he died. Unarmed RAMICOSM member Leroy Joseph was decapitated, while RAMICOSM second-in-command Nixon François was shot. In the ruins of the burned-out commissariat, Bale Wouze members gang-raped a 21-year-old woman, while other residents were gunned down by police and armed civilians firing from a helicopter as they tried to flee over a nearby mountain.

I was living in Haiti, reporting, at the time. When the photojournalist Alex Smailes and I arrived in the town a few days later, we found the USGPN and Bale Wouze patrolling Saint-Marc as a single armed unit. Speaking to residents there – against a surreal backdrop of burned buildings, the stench of human decay, drunken gang members threatening our lives with firearms and a terrified population – we soon realized that something awful had happened in Saint-Marc.

[These events are extensively chronicled in my two books on Haiti, Notes From the Last Testament: The Struggle for Haiti (Seven Stories Press, 2005) and Haiti Will Not Perish: A Recent History (Zed Books, 2017).]

“These people don’t make arrests, they kill,” a local priest, Père Arnal Métayer, told me at the time.

Alex and I were not the only journalists to document what was happening. The Miami Herald’s Marika Lynch wrote of how the town was “under a terrifying lockdown by the police and a gang of armed pro-Aristide civilians” and that “the two forces are so intertwined that when [Bale Wouze’s] head of security walks by, Haitian police officers salute him and call him commandant.” Gary Marx of the Chicago Tribune wrote of how “residents saw piles of corpses burning in an opposition neighborhood and watched as pro-Aristide forces fired at people scurrying up a hillside to flee.”

According to Anne Fuller, a Haiti veteran, fluent Creole speaker and a member of a Human Rights Watch delegation that visited Saint-Marc a month after the killings, at least 27 people were murdered there between 11 February and 29 February. Her conclusion was supported by the reporting of the respected Haitian journalist Nancy Roc, who wrote at the time “if justice is not rendered in the case of the La Scierie Massacre, we can fear the worst for the future” and by the research of the National Coalition for Haitian Rights (NCHR), a Haitian human rights organization (which has since 2004 been called the Réseau National de Défense de Droits Humains or RNDDH).

On 29 February, with his enemies closing in, Aristide and his family fled the country, leaving behind partisans at the mercy of the rebels and the multifaceted forces that had ousted him, and, in a final gesture of contempt, $350,000 in rotting U.S. currency found by looters in a safe behind a concrete wall at his mansion outside Port-au-Prince. A shipment of arms from the government of South African President Thabo Mbeki, routed through Jamaica with the connivance of Jamaican Prime Minister P. J. Patterson, appeared too late to save him.

In the ensuing months, Clunie Pierre Jules, a judge tasked with investigating the La Scierie killings, would announce that, in the court’s estimation, a massacre had indeed taken place, with at least 44 killed over a series of days, perpetrated by the PNH, National Palace security services, Bale Wouze and various armed civilians from Port-au-Prince.

The judge’s report listed a ghastly series of beheadings, rapes and other crimes, and said that Yvon Neptune’s declarations before the court and others regarding the killings revealed “glaring contradictions,” and that, between 7 February and 13 February 2004, phone records from his mobile showed that he had spent over nine hours on the phone to police and members of Bale Wouze in Saint-Marc. The judge concluded that sufficient evidence existed to charge 29 people, including Bale Wouze members Amanus Mayette, Biron Odigé, Roland “Black Ronald” Dauphin and Figaro Désir, former Aristide government officials such as Neptune, former PNH head Jean-Claude Jean-Baptiste, former Minister of Interior Jocelerme Privert and former Minister of Justice Calixte Delatour, and a number of others, including an American pilot, Ron Lusk, who had been working with the government. The judge said that insufficient evidence existed to charge Aristide himself and a number of others. In an interview with Radio Métropole, Calixte Delatour said flatly that the former president was directly responsible for the massacre in La Scierie, explaining that “everything went through Aristide, not because he was the president but because it is the tradition in Haiti; Jean-Bertrand Aristide is the main culprit of the massacre of La Scierie.”

For the victims and survivors of La Scierie, however, the story was far from over.

III. “What justice should we expect?”

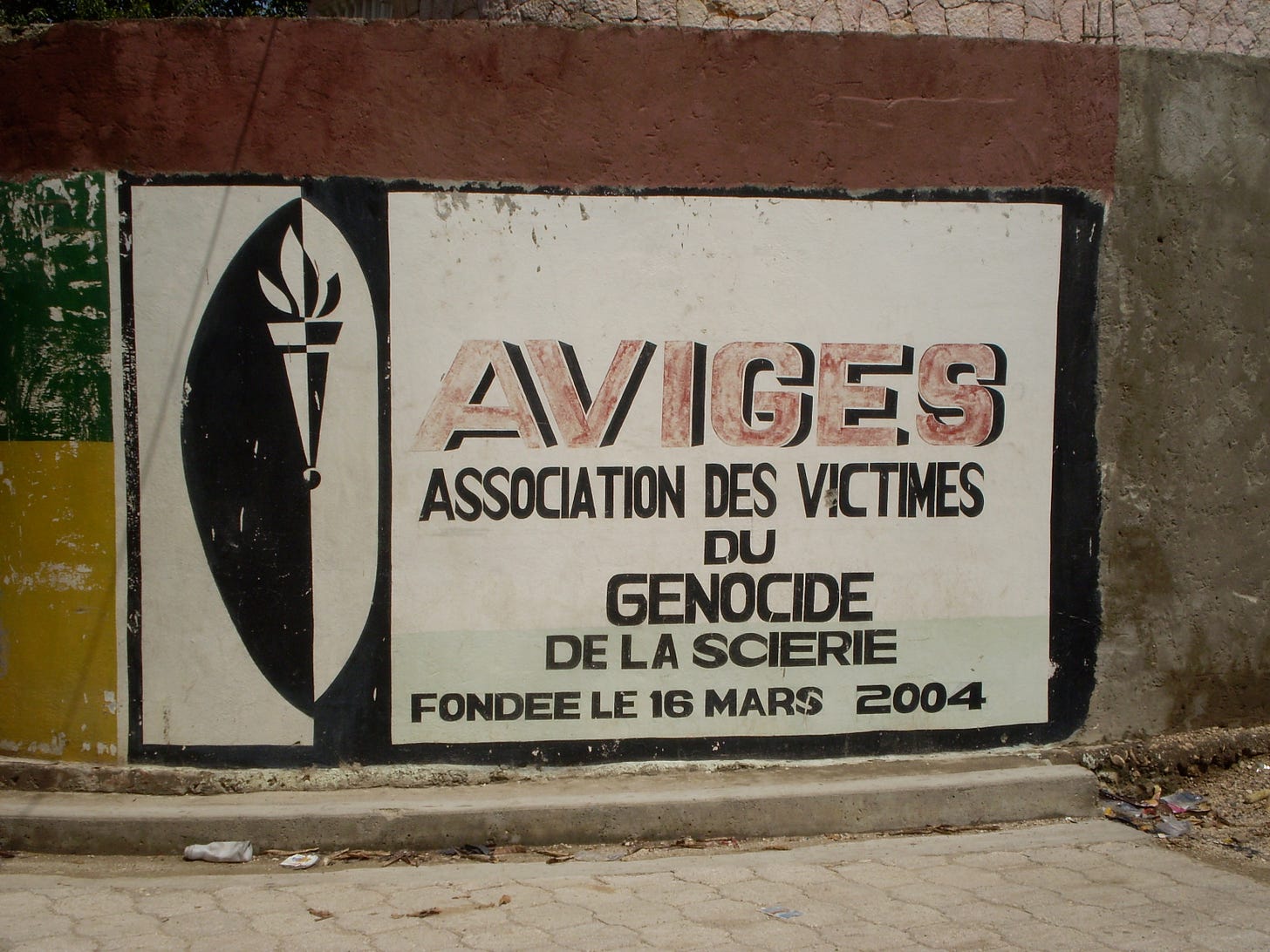

Survivors of the La Scierie massacre and relatives of the victims formed a solidarity organization, the Association des Victimes du Génocide de la Scierie (AVIGES), to petition the new interim government for justice. Both Yvon Neptune and Jocelerme Privert would eventually be arrested for their alleged roles in the La Scierie killings and held for months without charge. Neptune was detained in a palatial house in the middle class Pacot neighborhood (where I used to live) – referred to on Haitian radio as “a golden prison” – where he was to await trial and where he periodically announced he was going on hunger strike to protest his imprisonment. Called multiple times to answer questions from the judge at Saint-Marc, each time he refused. Writing for the Centre Œcuménique des Droits Humains (CEDH) in May 2005, the human rights activist Jean-Claude Bajeux urged Haiti’s government to “exert the greatest diligence so that those responsible for those murders [in Saint-Marc] be prosecuted fairly and properly.”

As the survivors of La Scierie fought their battle for justice, they were actively undermined by some in the international human rights community. This was especially true of so-called human rights organizations with deep financial and personal links to the Aristide regime such as the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti (IJDH), an ostensible human rights body co-founded by Aristide’s Miami attorney Ira Kurzban, who also served as the first president of its board of directors. During Aristide’s second term in office, Kurzban’s Miami law firm had received millions from the Aristide government for its lobbying work alone and Kurzban would continue to represent Aristide in a personal capacity for years thereafter. IJDH would write fawningly of Bale Wouze’s Ronald Dauphin - who went through a cycle of arrests, escapes and rearrests - as “a Haitian grassroots activist, customs worker and political prisoner.” The attorney Mario Joseph of IJDH’s partner organization, the Bureau des Avocats Internationaux (BAI), served as Dauphin’s attorney, preparing a “legal analysis” of the case, while also conveniently serving as another one of Aristide’s attorneys for many years, as well.

By August 2005, AVIGES head Charliénor Thomson was denouncing what he called a plan by the international community and the interim government to deny justice to the victims of the killings. With many powerful people, including many at the Mission des Nations Unies pour la stabilisation en Haïti (MINUSTAH) peacekeeping mission, clearly anxious to make a troublesome, complex case go away in the interest of holding elections, the UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in Haiti, Louis Joinet, caused outrage when, after meeting briefly (and only once) with survivors of the La Scierie massacre, he dismissed the killings as merely “a clash.” The AVIGES criticism was echoed by RNDDH, which said that the attitude of MINUSTAH chief Juan Gabriel Valdés and Haiti’s Minister of Justice Henry Dorléans to the case was “a scandal” and that, by pressuring for Neptune’s release, MINUSTAH and the interim government “sought to perpetuate impunity in Haiti.”

By the summer of 2006, following the inauguration of René Préval as Haiti’s new president, former Minister of the Interior Jocelerme Privert would walk out of prison a free man. He had been in jail for a little over two years. Shortly thereafter, Yvon Neptune, who had been not only Prime Minister but head of the Conseil Superieur de la Police Nationale d’Haïti at the time of the killings, was also free. The Assistant Secretary General of the Organization of American States (OAS), Surinamese diplomat Albert R. Ramdin, said that the release was “a very positive development” in a statement that nowhere mentioned the victims of La Scierie of their quest for justice. Neither man ever faced trial.

Weighing in on the release of Neptune and Privert, Human Rights Watch noted that “the La Scierie case was never fully investigated and the atrocities that the two men allegedly committed remain unpunished.” At the time Aristide himself was enjoying a lavish exile in South Africa.

Shortly after the release of Neptune and Privert, Hugues Saint-Pierre, the president of the Gonaïves court of appeal and head of the faculty of law and economics in the city, who was due to issue a final ruling on the La Scierie case, was killed when he was struck by a vehicle while waiting at a tap-tap stand. Saint-Pierre, by all accounts a rare honest and humble judge who had never been able to afford a car and usually traveled by either bicycle or public transportation, had been summoned to the capital by judicial authorities, including Justice Minister René Magloire, who were preparing to make a final decision on the La Scierie case. (Magloire later denied having summoned him.) Samuel Madistin, one of the attorneys for the victims in Saint-Marc, openly called Saint-Pierre’s death “suspicious.” When government officials appeared at Saint-Pierre’s funeral in Gonaïves, the people there threw stones at them.

Two days after Hugues Saint-Pierre died, Bale Wouze founder Amanus Mayette walked out of prison a free man, liberated by Saint-Marc judicial official Ramon Guillaume under questionable circumstances. RNDDH denounced the release as “arbitrary” and a move that would “strengthen corruption” and “allow the executioners of La Scierie to enjoy impunity,” asserting that “the government is trying to prevent the trial for the massacre of La Scierie.” Relatives of those who had been killed staged a sit-in in front of the Palais de Justice in Saint-Marc, calling for an explanation of Saint-Pierre’s death and the removal of Ramon Guillaume and government commissioner Worky Pierre (no relation), who they charged with subverting their quest for justice.

IV. “We demand justice because we have never had it”

In May 2009, I returned to Haiti from Paris, where I was living at the time, and I returned, once again, to La Scierie. Doing north along Route Nationale 1 - travel on which today is a life-or-death roll of the dice with a patchwork of brutal gangs who control the road - swirls of dust kicked up by the wind and passing tap-taps were juxtaposed with the gorgeous shimmering blue Caribbean. One passed the raucous, filthy market at the town of Cabaret, and the former mansion of dictator Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, now the embarkation point for ferries to Île de la Gonâve.

Once in Saint-Marc, I met AVIGES coordinator Charliénor Thomson and we walked into La Scierie together. Eventually, we came upon the burned-out RAMICOSM headquarters, which had been turned into something of a memorial to the victims, with an AVIGES mural, an image of a flaming torch and the words “Founded 16 March 2004.” Soon we were joined by another man.

“They came here and they massacred people,” 44-year-old Marc Ariel Narcisse told me. He wore a T-shirt reading “We won’t forget 11 February 2004” in Creole. “A grenade thrown into my mother’s house exploded, and the house caught fire. My cousin, Bob Narcisse, was killed there.”

I wandered over to visit Amazil Jean-Baptiste, whose 23-year-old son, Kenol St. Gilles, had been shot, beaten unconscious and then thrown into a burning cement depot, where he was incinerated, by Bale Wouze members. In contrast to the air-conditioned luxury in which most foreign human rights “experts” existed in Haiti during their trips there of a few days, Jean-Baptiste lived in a dilapidated structure without running water. She was 49 but looked at least a decade older, wearing a threadbare skirt, a T-shirt and sandals.

“They killed my boy and burned my boy,” she told me, as we stood in the half-finished entrance of the building. “And I am still suffering. We need justice, we demand justice, because we have never had it. I just want justice for my son.”

The next day, I sat discussing the case with RNDDH’s Pierre Espérance in the group’s Port-au-Prince office. While international groups had all but ignored the La Scierie massacre – more concerned with the accused held in jail without trial than with justice for the victims of the massacre itself – RNDDH had been pushing for justice for five years at that point, with little to show for their efforts. Finally, during a lull in our conversation, Espérance looked off into space as if deep in thought and then spoke.

“In our system, the criminal becomes a victim because the system doesn’t work.”

IV. The Ghosts of La Scierie

Time passed and the world moved on.

In 2011, Aristide returned to Haiti from his exile in South Africa. Since his return, he has been involved in several criminal trials - including one centering on the April 2000 murder of journalist Jean Léopold Dominique in which nine of Aristide’s close allies were indicted and during which the BAI’s Mario Joseph represented him - but never convicted. Despite Lavalas being a shadow of the party it once was (in Haiti’s last presidential election, its chosen candidate, Maryse Narcisse, received only 9% of the vote), the man still has his fans and apologists, especially abroad. Many anglophone historians of modern Haiti turn mush-mouthed and equivocating when asked to assess the man’s 2001 to 2004 term in office, and, as recently as May 2022, no less an outlet as The New York Times ran a deeply mendacious and dishonest article about the man, his tenure and his legacy authored by journalists Constant Méheut, Catherine Porter, Selam Gebrekidan and Matt Apuzzo.

After running a failed campaign for Haiti’s president, Yvon Neptune largely retired from politics.

Jocelerme Privert served as a Senator in Haiti's parliament from April 2011 until January 2016, and as that body's president from January 2016 until February 2016. In February 2016, amid disputed elections following the presidency of Michel Martelly, Jocelerme Privert became the interim president of Haiti, a post he held until February 2017. His ascent to the presidency was largely welcomed by the international community, for, in the years since 2004, Haiti’s political culture has continued to deteriorate to such a degree that men like Privet is now looked upon as a relative moderate. None of the foreign diplomats who met regularly with Privet dared breathe a word about La Scierie. It was as if the massacre never happened.

No other foreign journalist, no foreign human rights organization, no newspaper and no head of state will bother to remember the people of La Scierie today. There is no one outside of Haiti who thinks the lives of a bunch of nobodies who died in a town most foreigners have never heard of two decades ago are worth remembering. But they are worth remembering. They had value.

If the those at La Scierie had seen justice, perhaps the hell that Haiti is living through today - and the years since in which the gang model that tore La Scierie apart spread through the body politic until it became larger than the politicians, larger than politics and larger than the state itself - might have been avoided. Perhaps all those sent to die terrible, criminal deaths in places like Cité Soleil, La Saline, Croix-des-Bouquets, Grand Ravine, Ti Bois and elsewhere since then might have had a chance.

In 1998, in their song “Imamou Lele,” the Haitian band Boukman Eksperyans sang Gade bèl tèt nonm k-ap gaspiye la...Gade bèl gason k-ap gaspiye la/Gade bèl jenn fanm k-ap gaspiye la/Sa se enèji k ap gaspiye/Gade ayiti k-ap gaspiye la (Look at the intelligence that’s being squandered...Look at the handsome boys who are being lost/Look at the beautiful young ladies who are being mistreated/That’s energy that’s being wasted Look at Haiti that’s being wasted here).

Twenty years later, it still takes time to get one’s head around what happened in La Scierie and the enormity of the injustice that followed and still continues today. As the lyrics quoted suggest, what I am left with is an enormous sense of waste. Of human potential. Of a chance to break the country’s cycle of impunity that went unseized. Of the lives of so many people who dared rise up against a tyranny and paid the ultimate price for it.

This is not much of a memorial or a eulogy, for justice, real justice, is the only kind of homage that truly matters, but it is the only one that is in my power as a journalist and author to bestow so, along with my two books that recount it, here this tribute will remain until the forces within and without Haiti that have denied justice to the unquiet dead of La Scierie make amends and perform penance for their great betrayal. Perhaps as long as these words remain the people of La Scierie will never truly be forgotten by everyone and perhaps if you, as a reader, are reading these words about them, those who once lived, even in such a terrible time, will never truly be dead.

[Author’s Note: For a greater understanding of the 2001 to 2004 era in Haiti, in addition to my own books, I recommend two other books by journalists who were actually on the ground at the time, Gerry Hadden’s Never the Hope Itself: Love and Ghosts in Latin America and Haiti (Harper Perennial, 2011) and Kathie Klarreich’s Madame Dread (Bold Type Books, 2005), as well as the Trinidadian diplomat Reginald Dumas’ memoir An Encounter With Haiti (Medianet, 2008) and the historian Alex Dupuy’s The Prophet and Power: Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the International Community, and Haiti (Rowman & Littlefield, 2006). I also recommend four films: Arnold Antonin’s GNB Kont Attila (2004), Charles Najman’s La fin des chimères? (2004), David Adams’ Failing Haiti (2005) and Asger Leth’s Ghosts of Cité Soleil (2006).]