No, Chomsky

The revelations about the linguist’s relationship with the predator Jeffrey Epstein are a fitting epitaph to a disgraceful career.

Twenty years ago, I published my first book, Notes from the Last Testament: The Struggle for Haiti (Seven Stories Press), my chronicle of the political maelstrom that Caribbean nation experienced between the years of 1994 and 2004, a substantial part of which I spent living there. With a thoughtful forward by the filmmaker Raoul Peck (who graciously concluded that it managed “to show in the most intimate details how a democratic movement went wrong and how a heritage of valuable victories and painful sacrifice was slandered by a charismatic leader and his cronies”), the book was chiefly a depiction of the years between the return of Jean-Bertrand Aristide to Haiti by a U.S.-led multinational force in 1994 and his overthrow and exile amid massive street protests against his rule and an armed rebellion - initially started by street gangs that he helped create and whose successors continue to haunt the country today - a decade later. Within that narrative framework, I did my best to talk to as many as Haitians from as many strata of society as I possibly could, from peasant activists to feminist leaders to journalists to taxi drivers to laborers to political actors to artists to many of the young men who made up the initial wave of the gangs, who then were referred to as chimere, after a mythical fire-breathing demon and who were succored by Mr. Aristide and his Fanmi Lavalas political party. In the process, I had some very unflattering things to say about many of those who had continued to carry water for the Haitian leader in the U.S. long after he had gone very publicly and dramatically bad in Haiti itself or, as the Trinidadian diplomat Reginald Dumas wrote in his own book, An Encounter With Haiti, after Aristide “[acquired] for himself a reputation at home which did not match the great respect with which he was held abroad.”

As with any new author, I was wondering whether anyone would even read the book at all, so I was quite surprised when it turned out that the American linguist Noam Chomsky was apparently among my initial audience, mentioned as he was in two (rather unflattering) paragraphs in the book’s 454 pages, where I took him to task for what I viewed as a lazy and uncomprehending view of Haiti’s intensely complex political and cultural reality. As the book was published, admitting that they themselves had not even read it in its entirety, Chomsky and his then-literary agent, Anthony Arnove, launched what can only be described as a minor campaign against it, berating my publisher (which also published several Chomsky titles) over its contents and attempting, so it seemed, to scuttle its publication, or at least the press support of it. I confess I was surprised that Chomsky even knew who I was, but it did give me some insight into the thin-skinned, priggish nature of the man who in the years thereafter would go on to dramatically reinforce the grounds for the criticism I had made of him all those years ago.

For far too long (and long before I crossed paths with him), Chomsky was held up as some kind of example of principled contrarianism by too many on the left and wrongly credited as being someone who bravely spoke truth to power, largely emanating from his early activism opposing the catastrophic activities of the United States during the Vietnam War and its subsequent illegal expansion of that conflict into neighboring Cambodia. However, very soon after these early days, when Chomsky was just one of many speaking out against the conflict, there were signs of an amoral blindness and a deference to perceptions of power and privilege (usually his own) that led him to ignore and often actively deny the suffering of others if it did not fit into what was a binary, Manichaean view of the world where those he perceived of as enemies (usually the United States or its allies) were the font of all evil and all praise was due to him for having the wisdom and courage to dare to point this out.

In 1975, the Communist Party of Kampuchea - better known as the Khmer Rouge - seized power in Cambodia. During the next four years, in an attempt to achieve “Year Zero” - that is, a complete destruction of the previously existing culture and traditions of the nation - the Khmer Rouge “subjected the country’s citizens to forced labor, persecution, and execution in the name of the regime’s ruthless agrarian ideology,” as noted on the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. It was a genocide in which almost two million people - approximately one third of the country’s population - died and which only stopped when the Vietnamese military invaded the country and succeeded in toppling the Khmer Rouge in January 1979. The killings were extensively documented by journalists such as Fox Butterfield, Sydney Schanberg and Elizabeth Becker, and by the voluminous testimony hundreds of thousands of Cambodians fleeing the horrors of the regime. Today, one can visit the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh, the site is a former secondary school that was used as a torture and execution centre by the Khmer Rouge known under the moniker Security Prison 21 (S-21).

In June 1977 - at the height of the genocide - in an article in The Nation co-written with the economist Edward S. Herman titled “Distortions at Fourth Hand,” Chomsky and Herman praised the book Cambodia: Starvation and Revolution by Gareth Porter and George C. Hildebrand, which they called as “a carefully documented study of the destructive American impact on Cambodia and the success of the Cambodian revolutionaries (i.e the Khmer Rouge) in overcoming it.” The month before, Porter had lied to the U.S. Congress that “the notion that the leadership of Democratic Kampuchea [as the the Khmer Rouge had named their regime] adopted a policy of physically eliminating whole classes of people, of purging anyone who was connected with the Lon Nol government, or punishing the entire urban population by putting them to work in the countryside after the ‘death march’ from the cities, is a myth.”

Granting that they did “not pretend to know where the truth lies amidst these sharply conflicting assessments,” in their article, Chomsky and Herman nevertheless evoked “highly qualified specialists” who, they claimed, “concluded that executions have numbered at most in the thousands; that these were localized in areas of limited Khmer Rouge influence and unusual peasant discontent” and then alleged that “repeated discoveries that massacre reports were false.” Chomsky and Herman then go on to largely dismiss the first-hand accounts those fleeing the genocide due to “the extreme unreliability of refugee reports, and the need to treat them with great caution…Refugees questioned by Westerners or Thais have a vested interest in reporting atrocities on the part of Cambodian revolutionaries.” As the article continues, Chomsky and Herman make increasingly delirious claims, including that “the ‘slaughter’ by the Khmer Rouge is a…New York Times creation” and “the bulk of these deaths are plausibly attributable to the United States.”

François Ponchaud, a French Catholic priest and missionary to Cambodia who had documented the genocide and whose book Cambodge année zéro (Cambodia: Year Zero) Chomsky and Herman had criticized in the same article where they praised Porter and Hildebrand, subsequently wrote that Chomsky and Herman were “two ‘experts’ on Asia [who] claim that I am mistakenly trying to convince people that Cambodia was drowned in a sea of blood…For them, refugees are not a valid source ... It is surprising to see that ‘experts’ who have spoken to few if any refugees should reject their very significant place in any study of modern Cambodia. These experts would rather base their arguments on reasoning: if something seems impossible to their personal logic, then it doesn’t exist.”

According to the academic Donald Beachler, a specialist on genocide studies, Chomsky’s campaign to protect the Khmer Rouge went far beyond the occasional article and extended to writing letters to editors and publications “to urge discounting atrocity stories” some of which ran “as long as twenty pages.”

Lest readers think this was a one-off collaboration, Chomsky and Herman continued to inveigh about Cambodia in their highly-inexpert fashion (neither spoke Khmer or had spent any time in “Democratic Kampuchea,” as the as the Khmer Rouge had rechristened the country) in a pair of 1979 books, The Political Economy of Human Rights, Volume I: The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism and The Political Economy of Human Rights, Volume II: After the Cataclysm: Postwar Indochina and the Reconstruction of Imperial Ideology. In 1988, Edward S. Herman was also the co-author of perhaps Chomsky’s most well-known book, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media.

Thus, one already sees at the time of the publication of The Nation article, now nearly fifty years ago, the pattern Chomsky would more and more adhere to as his career went on: The reporting of journalists on the ground and that of citizens of the countries in question themselves could be ignored, dismissed or derided if it lent itself to a more complex picture than the one Chomsky obsessively adhered to, that of the United States - and the United States alone - being the world’s unique supervillain. From his sinecure at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he taught from 1955 until 2002, Chomsky appeared to believe that his pronouncements, even about places he knew almost nothing about and whose histories and cultures he was surpassingly ignorant of, must be treated as the utterances of a wise sage.

Regarding the Bosnian War that raged between 1992 and 1995, Chomsky (along with Arundhati Roy, Tariq Ali, John Pilger and others) signed his name to a letter praising Diana Johnstone’s 2002 book Fools’ Crusade: Yugoslavia, NATO and Western Delusions (Pluto Press) as “an outstanding work, dissenting from the mainstream view but doing so by an appeal to fact and reason, in a great tradition.” In the book, Johnstone falsely argued that the July 1995 killing of at least 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys by Bosnian Serb forces in Srebrenica was not “part of a plan of genocide” and that “there is no evidence whatsoever” for such a charge. 18 people would subsequently be convicted before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia for crimes committed in Srebrenica, including Radovan Karadžić, former “president” of the breakaway Republika Srpska during the Bosnian War, convicted of genocide, and former Army of Republika Srpska leader Ratko Mladić, also convicted of genocide.

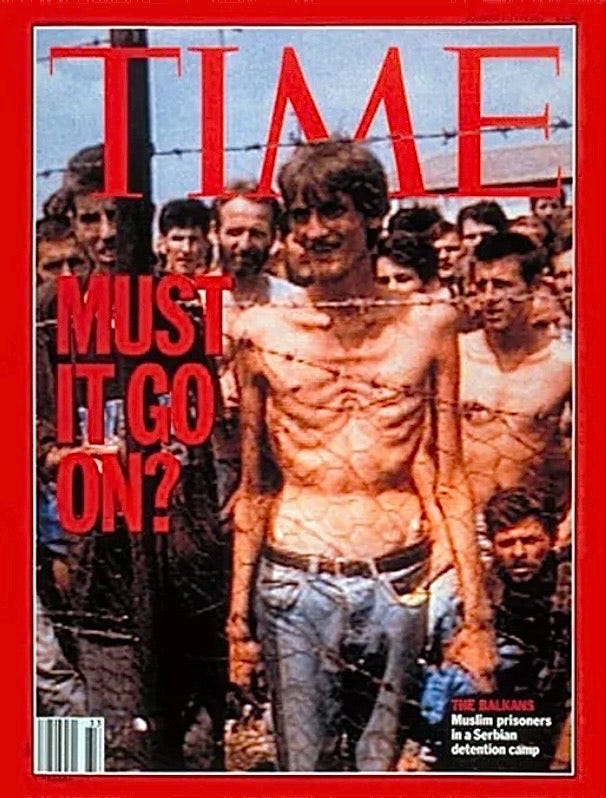

Elsewhere in her book, Johnstone also states - again, falsely - that no evidence existed that much more than 199 men and boys were killed there and that Srebrenica and other unfortunately misnamed “safe areas” had in fact “served as Muslim military bases under UN protection.” When outrage followed Johnstone repeating her ravings in the left-wing Swedish magazine Ordfront in 2003, Chomsky felt exercised enough to write a personal letter to the publication defending the author’s genocide denial, writing at the time “I have known her for many years, have read the book, and feel that it is quite serious and important.” Chomsky was also among those who supported a campaign defending the right of a fringe magazine called Living Marxism to publish claims that footage the British television station ITN took in August 1992 at the Serb-run Trnopolje concentration camp in Bosnia was faked. ITN sued the magazine for libel and won, putting the magazine out of business, as Living Marxism could not produce a single witness who had seen the camps at first hand, whereas others who had - such as the journalist Ed Vulliamy - testified as to their horror. In 2006, in an interview with Radio Television of Serbia (a station formerly aligned with the murderous and now-deceased Serbian dictator Slobodan Milosevic), Chomsky stated, of the iconic, emaciated image of a Bosnian Muslim man named Fikret Alic, the following:

Chomsky: [I]f you look at the coverage [i.e. media coverage of earlier phases of the Balkan wars], for example there was one famous incident which has completely reshaped the Western opinion and that was the photograph of the thin man behind the barb-wire.

Interviewer: A fraudulent photograph, as it turned out.

Chomsky: You remember. The thin men behind the barb-wire so that was Auschwitz and ‘we can’t have Auschwitz again.’

In taking this position, Chomsky again seemingly attempted to dismiss the on-the-ground reporting of not only Mr. Vulliamy - whose work on the war in Bosnia won him the British Press Awards International Reporter of the Year Award - but of other journalists such as Penny Marshall, Ian Williams and Roy Gutman. In fact, Vulliamy, who filed the first reports on the horrors of the Trnopolje camp and was there that day the ITN footage was filmed, wrote in March 2000:

Living Marxism’s attempts to re-write the history of the camps was motivated by the fact that in their heart of hearts, these people applauded those camps and sympathized with their cause and wished to see it triumph. That was the central and - in the final hour, the only - issue. Shame, then, on those fools, supporters of the pogrom, cynics and dilettantes who supported them, gave them credence and endorsed their vile enterprise.

In an October 2005 interview with the Guardian’s Emma Brockes, Chomsky condescendingly stated that “Ed Vulliamy is a very good journalist, but he happened to be caught up in a story which is probably not true.” This interview in particular became the focus of such a relentless campaign by Mr. Chomsky and his cult-like supporters that the paper, to its eternal shame, pulled it from its website and issued what can only be described as a groveling apology that did a great disservice to the reporters who actually risked their lives covering the Bosnian conflict and the victims of the conflict themselves.

The Guardian controversy prompted Kemal Pervanic, author of The Killing Days: My Journey Through the Bosnia War, and a survivor of the Omarska concentration camp, to write that “If Srebrenica has been a lie, then all the other Bosnian-Serb nationalists’ crimes in the three years before Srebrenica must be false too. Mr Chomsky has the audacity to claim that Living Marxism was ‘probably right’ to claim the pictures ITN took on that fateful August afternoon in 1992 - a visit which has made it possible for me to be writing this letter 13 years later - were false. This is an insult not only to those who saved my life, but to survivors like myself.”

But Chomsky’s endorsement of genocide denial vis-a-vis the Bosnian war would not stop there. In 2010, his old collaborator Edward S. Herman, co-authored a book with David Peterson called The Politics of Genocide, to which Chomsky wrote the forward. In it, the authors, to cite just a few examples, falsely claim that the judgement in the trial of Army of Republika Srpska’s Radislav Krstić - the first man convicted of genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia - “argued that…incontestably [the Serbs] had not killed any but ‘Bosnian Muslim men of military age.’” The trial judgement says no such thing. Hard as it may to believe, the book gets worse, far worse, when the authors turn their attention to the 1994 Rwandan genocide, when upwards of 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were slaughtered by military, milita and ordinary citizens in a carefully-planned explosion of ethnic murder by Hutu supremacist elements. Herman and Peterson, though, claim that this was merely a “propaganda line on Rwanda that turned perpetrator and victim upside-down” and that “that the great majority of deaths were Hutu, with some estimates as high as two million.”

This is pure genocide-denying poision to which Chomsky gleefully added his own endorsement. In his overlong and discursive foreword to Herman and Peterson’s book, Chomsky claims the global political commitment (known as the Responsibility to Protect) endorsed by the United Nations in 2005 asserting every state has a responsibility to protect its population from four mass atrocity crimes - genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity - is, in fact, “a guiding imperial doctrine, invoked to justify the resort to violence when other pretexts are lacking.” He then goes on to quote approvingly from Herman and Petereson’s text that “the word ‘genocide’ has increased in frequency of use and recklessness of application so much so that the crime of the 20th Century for which the term was originally coined often appears debased” and, in his own words, to sulk about “the vulgar politicization of the concept of genocide.”

In a subsequent 2011 exchange of emails with the journalist George Monbiot about his endorsement of the book, Chomsky wrote that U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s atrocious military support of Guatemala dictator Efraín Ríos Montt during the latter’s genocidal war against that country’s indigenous citizens in the early 1980s, among other U.S. misdeeds, was “incomparably more significant than the question of how many people Serbs ‘executed’ at Srebrenica as distinct from killing them in combat…and whether the huge number slaughtered in Rwanda…were mostly Hutu or mostly Tutsi.”

It is, again, an astonishing display of intellectual and moral bankruptcy and barrenness but one that, again, should not have surprised anyone who had been paying attentions to Chomsky’s statements over the years. In sum, what Chonsky is saying that “The dead that support my political arguments - for I am a Great Man with Important Thoughts - have much more worth than those who don’t.”

Which brings us - finally - the nature of Chomsky’s relationship with the criminal sexual predator Jeffrey Epstein. As reported in Julie K Brown’s essential “Perversion of Justice” series of articles in the Miami Herald, from which the following timeline is drawn, around the same time that Chomsky’s repellent negationist views on the Bosnian genocide were becoming more widely known, in March 2005, a 14-year-old girl and her parents reported Epstein had molested her after she had been taken to his Palm Beach mansion by a female classmate to give Epstein a massage in exchange for money. The following month, Palm Beach police began an intense investigation into Epstein, interviewing a number of girls who had visited Epstein’s home, his staff, executing a search warrant on his Palm Beach home and signing a “probable cause” affidavit charging Epstein and two of his assistants with multiple counts of unlawful sex acts with a minor, which the Palm Beach state attorney, Barry Krischer, inexplicably then instead referred to a grand jury instead of acting on. The jury heard from only one girl and issued an indictment on a single count of solicitation of prostitution, despite the fact that Epstein’s repeated abuse of multiple minors had now been documented by law enforcement. In July 2006, the FBI began a federal investigation into Epstein and began interviewing potential witnesses and victims in locales ranging from Florida to New York to New Mexico, all places where Epstein maintained residences.

As the U.S. Attorney’s Office prepared a 53-page indictment, then-United States Attorney for the Southern District of Florida Alexander Acosta (who later served as Donald Trump’s Secretary of Labor during his first term) repeatedly met with Epstein’s defense team. As negotiations dragged on for months, the U.S. Attorney’s Office noted that “Epstein’s victims are being harassed by [Epstein’s] lawyers.” In June 2007, Epstein pleaded guilty to a single state charge of solicitation of prostitution and one count of solicitation of prostitution with a minor under the age of 18, followed by a sentence of 18 months in jail, a year of community control or house arrest and registration as a convicted sex offender. Epstein’s victims were not informed about this deal until after it was already concluded. Thus began a desperate, decade-long effort by a group of incredibly brave women to hold Epsetin to account for having raped them and others when they were children and having pimped them out to other powerful, privileged men.

During this time, as is attested to by the emails among tens of thousands of pages of documents procured from Epstein’s estate released by the House Committee on Oversight last month [documents that also reinforced the depth of Epstein’s involvement with figures such as Donald Trump, Bill Clinton and Bill Gates), Noam Chomsky began what was clearly a close personal relationship with Epstein, who provided him with the absolute deference to his political pronouncements that Chomsky so clearly craved.

On 24 December 2015, Chomsky writes in a chummy tone to Epstein of how “Iran…has not been involved in terrorism” (which must come as news to the families of the 85 people killed by Iranian agents at the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina in Buenos Aires in July 1994), before the two digress to a discussion of linguistics with Epstein creepily observing “we don’t teach children to see.” Boasting of his supposed all-seeing lucidity after the signing of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal between the government in Tehran and various foreign nations - most notably the United States - Chomsky writes to Epstein on 10 August 2015 that Iran’s “strategic doctrine is defensive,” which, again, must have come as a surprise to the Syrians that Iranian forces helped ethnically cleanse from areas like Al-Zabadani and Darayya as it fought to defend the government of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad during Syria’s civil war, or the Iraqis murdered, tortured and disappeared by the militias like Kata’ib Hezbollah that its regime helped organize. Chomsky then returns to his tired talking points that “reading the US and UK press is like living in some lunatic asylum. I’m wondering whether to write about it again; have done so repeatedly. It’s like talking to a wall.”

On 5 August 2015, Epstein advises Chomsky “Only go to Greece if you feel well, I just had to send my plane to bring another lefty friend back from Athens to see a Jew doctor in New York,” before continuing the following day “you are of course welcome to use apt in new york with your new leisure time, or visit new Mexico again.” Thus the reader is provided with apparent evidence that Chomsky spent time at at least one location - Epstein’s home, Zorro Ranch, in New Mexico - where accusers said Epstein is known to have raped and abused girls.

On 2 December 2015, Epstein writes to Lesley Groff “Do you know Chomsky, he Is with me.” Groff, along with three other women, was named as an unindicted co-conspirators in Epstein’s 2008 non-prosecution agreement and in a 2011 article in Politico described her as follows:

Groff…worked as Epstein’s executive assistant in Manhattan when she was in her 30s. According to court documents filed in a 2019 lawsuit by victim Jennifer Araoz, Groff was critical in facilitating Epstein’s sexual abuse. She looked after Epstein’s victims, booked their travel and made sure they maintained “rules of behavior,” according to another lawsuit. In a statement to POLITICO, Groff’s lawyer said she “never witnessed anything improper or illegal” while working for Epstein and that she has “always maintained her innocence” in the Araoz case. That case was dropped when Araoz accepted payment from the victims’ compensation fund, which has a provision saying applicants cannot sue Epstein’s employees.

The following year, on 25 June 2016, Epstein writes to Chomsky, referring to his travels earlier that summer, “what was the highlight.? caribean [sic] is close to brazil, if you wanted you are always welcome and valeria can meet you there,” to which Chomsky respond later that day “Highlight? A chance to spend some free time alone together. Some good concerts. An evening in a small café with jazz duo playing Brazilian jazz. Things like that. Still eager to make it to the Caribbean, but looks as though we’ll have to wait.”

The “Caribbean” that Chomsky was eager to make it to almost certainly refers to Little Saint James, the private island in the United States Virgin Islands which Epstein used as one of the bases for his underage sex trafficking operation. In 2019, a former air traffic controller who worked at Epstein’s private air stip on the island told Vanity Fair:

On multiple occasions I saw Epstein exit his helicopter, stand on the tarmac in full view of my tower, and board his private jet with children—female children. One incident in particular really stands out in my mind, because the girls were just so young. They couldn’t have been over 16. Epstein looked very angry and hurled his jacket at one of them.

At one point, an undated letter was drafted - whether it was written by Chomsky himself (it bears his name but not his signature) or by a third party in hopes he would attach his signature to it later is unclear - in which the Chomsky figure writes

I met Jeffrey Epstein half a dozen years ago. We have been in regular contact since, with many long and often in-depth discussions about a very wide range of topics, including our own specialties and professional work, but a host of others where we have shared interests. It has been a most valuable experience for me…I have learned a great deal from him about the intricacies of the global financial system, about complex technical issues that arise in the often arcane world of finance, and about specific cases in which I have a particular interest, such as the financial situation in Saudi Arabia and current economic planning and prospects there. Jeffrey invariably turns out to be a highly reliable source, with intimate knowledge and perceptive analysis, commonly going well beyond what I can find in the business press and professional journals….

Jeffrey has repeatedly been able to arrange, sometimes on the spot, very productive meetings with leading figures in the sciences and mathematics, and global politics, people whose work and activities I had looked into though I had never expected to meet them. Once, when we were discussing the Oslo agreements, Jeffrey picked up the phone and called the Norwegian diplomat who supervised them, leading to a lively interchange. On another occasion, Jeffrey arranged a meeting with former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, whose record I had studied carefully and written about. The impact of Jeffrey’s limitless curiosity, extensive knowledge, penetrating insights, and thoughtful appraisals is only heightened by his easy informality, without a trace of pretentiousness. He quickly became a highly valued friend and regular source of intellectual exchange and stimulation.

In March 2018, as was later reported by the Wall Street Journal, Chomsky received a transfer of approximately $270,000 from an account linked to Epstein, telling the Journal that it was “restricted to rearrangement of my own funds, and did not involve one penny from Epstein.” Chomsky would later say that the movement of money was to do with his “late wife Carol,” after whose death he “had to sort some things out. I asked Epstein for advice. There were no financial transactions except from one account of mine to another…These are all personal matters of no one’s concern.”

Three months after the transfer was made, in a 12 June 2018 text message to an undisclosed associate, Epstein writes “Spoke to Chomsky, he’s all in.” Exactly what Chomsky was “in” on remains unexplained.

As per a search of Epstein’s emails that have been released by the House, in February 2019, only months before he would be arrested again, Epstein arranged a meeting between Chomsky and former Trump strategist Steven Bannon that appears to have taken place in Tucson, Arizona on 9 February 2019. Bannon was in Arizona - where Chomsky had maintained an affiliation with the University of Arizona since 2017 - to attend a fundraiser in support of the erecting of a border “wall” on private land with private money. In a series of emails before the rendezvous, Bannon and Epstein exchanged some thoughts:

Bannon: I’’m in Tucson -- can Chomsky meet tomorrow afternoon???

Epstein: Yes, he’d like that. His wife is Brazilian so go gently re bolsonaro. They are friends with Lula. But he is an iconic figure and you shouldn’t pass up the chance to talk history and politics. I will connect you on email. So you can coordinate directly… He will want to know how if you are for the little guys- tax cut health care attack and bolsonari [sic] threats to organized workers

And then after the meeting:

Epstein: Well?

Bannon: Great gentleman…Love the wife…3 hour punch out

Epstein: Glad you had the opportunity- he could not choose a college major so hecreated a field from scratch/ linguistic s

Bannon: Brilliant--- but short on some basic facts…: 3 hours dude@ 90…I’m wasted.

Only two months later, Chomsky would stand before an audience at Old South Church in Boston and tell them

Today we do not—we are not facing the rise of anything like Nazism, but we are facing the spread of what’s sometimes called the ultranationalist, reactionary international, trumpeted openly by its advocates, including Steve Bannon, the impresario of the movement.

There was no mention of the long meeting with Bannon only weeks before, even less a mention that it was a meeting brokered by none other than Jeffrey Epstein.

Finally, in June 2019, Epstein was arrested and charged with sex trafficking of minors and conspiracy to commit sex trafficking of minors. Epstein subsequently died in his jail cell at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in Manhattan on 10 August 2019 under circumstances that remain the subject of fierce debate. Epstein’s accomplice in his abuse, Ghislaine Maxwell, was subsequently convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison for her role in helping Epstein sexually exploit and abuse multiple minor girls.

And Chomsky? In the years immediately preceding and following Epstein’s death, he continued his tradition of atrocity denial.

As the people of Syria struggled mightily to throw off the homicidal grasp of the inherited Assad dictatorship - fighting not only against Assad’s forces but also his Iranian, Lebanese and Russian allies - Chomsky was opining that “in Syria, Iran is supporting the official government [under Bashar al-Assad]...you can hardly accuse Iran of illegal or criminal behavior by supporting the recognized government.” In a 2015 lecture on “Identity, Power, and the Left: The Future of Progressive Politics in America” at Harvard, Chomsky again weighed in on the situation in Syria (a country, like most of those he commented on, that he had no expertise at all in) to declaim that Russia’s support of the Assad dictatorship - which netted the Kremlin access to a five decade-long lease on the port in Tartous, saw its military kill tens of thousands of Syrians and about which the Russian government itself boasted gave it the opportunity to test “more than 320 types of weapons” - was “not imperialism.” In May 2017, referring to the Khan Shaykhun chemical weapons attack by the Assad government the previous month, Chomsky told the radio programme Democracy Now! (itself often a font of atrocity denial and conspiracy theories) that “it’s not so obvious why the Assad regime would have carried out a chemical warfare attack at a moment when it’s pretty much winning the war, and the worst danger it faces is that a counterforce will enter to undermine its progress.” He then went on to endorse the work of retired MIT professor Theodore Postol, who claimed that the crater formed in Khan Sheikhoun after the attack was not that of an air-dropped bomb, as claimed by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), but rather from the impact of a 122 mm rocket. Responding to Postol’s claims, the investigative website Bellingcat concluded that the Postol co-authored “report” was “a document with so many grave and self evident errors” including the fact that “Postol does not present a single example of an improvised rocket motor armed with a factory manufactured 122 mm warhead.” Postol had previously suggested that August 2013 Sarin attacks in Damascus had been staged.

[Ironically, Chomsky was on Democracy Now! to promote his book Requiem for the American Dream: The 10 Principles of Concentration of Wealth & Power, which would be a succinct description of his relationship with Jeffrey Epstein.]

Chomsky’s Syria rhetoric was a stance that the analyst Sam Hamad characterized as “conservative, orientalist, and incoherent.” More expansively, in 2022, the great Syrian writer and leftist political dissident Yassin al-Haj Saleh wrote of how Chomsky “views the Syrian struggle - as with every other struggle - solely through the frame of American imperialism.”

Al-Haj Saleh then continued:

[Chosmky’s] perception of America’s role has developed from a provincial Americentrism to a sort of theology, where the U.S. occupies the place of God, albeit a malign one, the only mover and shaker…The ossification of Chomsky’s system of thought explains the paradox of labeling the regime brutal and monstrous without being able to say one positive sentence about any of those who have been struggling against it. He cannot be blind to the fact that the dynastic Assad regime is one of the worst on the planet. Chomsky is instead guided by a dead system that is unresponsive to people’s legitimate desire not to live under violent tyranny or to the scale of human suffering and pain inflicted upon them when they act upon that desire. The problem with Chomsky is not that he knows little about Syria (which indeed is the case); the problem is that he can never say, “I do not know.” Within his perspective, he is as omniscient as U.S. imperialism is omnipotent.

Not to leave the people of Ukraine outside of his scorn, only weeks before the second part of Vladimir Putin’s genocidal, imperialist invasion of the country (the first part of which began with Russia’s 2014 invasion of Donbas and occupation of Crimea), Chomsky said that Ukraine’s 2013-2014 Euromaidan protests and 2014 Revolution of Dignity - in direct response to President Viktor Yanukovych’s corruption, human rights abuses and attempts to drag Ukraine away from Europe and towards Russia - were “a coup with U.S. support…that led Russia to annex Crimea, mainly to protect its sole warm water port and naval base, and apparently with the agreement of a considerable majority of the Crimean population.” Noting the Chomsky’s comments left him “aghast,” the Ukrainian writer and translator Artem Chapeye (the nom de plume of Anton Vasilyovich Vodyanyi) responded by asking

What if the US occupied Baja, California? Before ‘overthrowing capitalism,’ try thinking of ways for us Ukrainians not to be slaughtered, because ‘any war is bad.’ I beg you to listen to the local voices here on the ground, not some sages sitting at the center of global power. Please start your analysis with the suffering of millions of people, rather than geopolitical chess moves. Start with the columns of refugees, people with their kids, their elders and their pets. Start with those kids in cancer hospital in Kyiv who are now in bomb shelters missing their chemotherapy.

Though many of his supporters and acolytes claimed to be “shocked” by the revelations of Chomsky’s relationship with Jeffrey Epstein, I was not. But the fact that I had Chomsky’s number two decades ago while many were still praising him in no way makes me feel joyful at the deformation of the man’s character being proven in such a vivid way. The important lesson I hope that people will take from this new information is that Noam Chomsky always thought some human lives were more valuable than others, and that has pretty much been the defining ethos of his life’s work.

The lives of Vietnamese killed by the atrocious war the U.S. waged in their country were useful to him as examples of the cost of U.S. empire, but the deaths of some 2 million people under the genocidal regime of Cambodia’s communist Khmer Rouge were not. The deaths of Iraqis killed by the criminal U.S. invasion there in 2003 were useful, but the deaths of Syrians groaning under the tyranny of the Assad dynasty were not. Ukraine? It was just another proxy for Chomsky to trot out his old, tired talking points, much the way a dipsomaniac at the end of the bar circles around the same handful of familiar stories again and again.

But the thing is, once you start viewing yourself as an arbiter capable of valuing and devaluing lives in such a way, as Chomsky made his career doing - and as has filtered down to many who claim to admire his “objective” analysis - you find it a small step to conclude that it’s not just the destruction of the lives of Cambodians, Bosnians, Rwandans and others that aren’t worth mourning, but that the destruction of the lives of the dozens and dozens of girls your fabulously wealthy new best friend raped don’t count for much, either. They also become meaningless distractions from the great men and their big ideas, with those left in their wake utterly unworthy of empathy or even consideration. Like political victims on the “wrong” side of history, so to do personal victims become expendable.

Far from being “the world’s top public intellectual,” as he was once named in a 2005 poll, Chomsky will be remembered as just another in a long line of wealthy and privileged men who believed that it was their right to trample on their perceived lessers as they left the world a little bit colder and crueler than they found it. Perhaps it is naive, but one hopes that perhaps this heartless and destructive world view will leave with him. I, for one, will not miss it.